“Right to Bear Alarms”

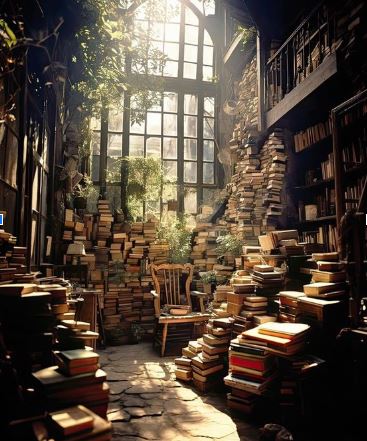

Students often feel like shadows or shells of themselves when battling mental health issues.

December 18, 2020

*Disclaimer: This article is intended for mature audiences only. It is a reflection of the relationship among mental health concerns, schools, and gun violence across the country, and NOT a commentary on East Rockaway Junior-Senior High School.

I march single file through a doorway laced in alarms, my dog tag hangs loosely around my neck. I peer down my school hallway, riddled with plastic sacks and anxious, drained, shells of humans, wondering which one of them will finally snap. If you’ve ever watched the news, then you’ve surely seen the headlines. Our children are slaughtering each other, and this prison-like wasteland is where we are sending them to do it. No matter how many attendance lists and hallway sweeps are performed, arming our schools solely through minuscule safety procedures is like bringing a knife to a gunfight. If said knife was built from bathroom sign-in sheets. Rather than continually adding multitudes of ineffective safety measures to our schools, we need to work on changing school culture and student-teacher relationships. In doing so, we can better keep our precious children safe, and hopefully erase the American high school’s penitentiary connotation that society has created.

It seems improper to be addressing school violence in a time in which many of our students aren’t even in schools, you may view it as something that doesn’t need to be prioritized. Seeing as we declined from 46 school shootings in 2019 to 8 so far in 2020 (CNN), from an outsider’s perspective, it would seem as if we had made some progress. However, these values do not account for what is to come when more students return to school, especially those students who have been negatively impacted by the coronavirus lockdown. It is human nature to crave interaction with other beings, and in the many months in which we were unable to do this, a plethora of adverse effects to mental health have sprung up nationally. For instance, being cooped up inside has led to greater usage of technology for many children, which has, in turn, led to psycho-social problems like Internet addiction, lower self-esteem, and low interest in physical activities (Marsden). Furthermore, rates of depression in all age groups skyrocketed during the pandemic, as many individuals had to gripe with the effects of fear, loss, isolation, financial concerns, and loss of everyday consistency. School violence and mental health have a direct scientific correlation, so with students re-entering school building still burdened with pandemic woes, we need to take direct action in treating them in order to discourage a new wave of violence.

You may have grown up around the motto “better safe than sorry.” It’s an ideal concept at first, but reliance on heavy safety seems to have the same effect on our schools as antibiotics have on the human body: they become just that, reliant. And as they are consistently added, their effect begins to diminish. Those who argue this point are struggling to realize that by keeping a tally on the exact actions of each individual student, you are not erasing the anger that causes Johnny to grab his father’s glock and pick off middle schoolers like target practice. Even though the armor is being added, a Harvard research study has reported that prior to 2020, school shooting rates have nearly tripled since 2011. These regulations are merely scraping the surface of what we would need to be utterly “protected”, and additionally do not prepare students for realistic situations after high school. Face it, we aren’t going to have everyone parading around Times Square in bubble wrap, in their own little Kevlar-coated forcefield from the outside world. What we can, and should do, is address why so many innocent children possess the urge to kill, not how to prevent them from acting on it.

Compare the adolescent mind to a flower: given a fresh seed and proper care, it will flourish. However, a rotten seed will never grow a ravishing red rose, no matter what you sugarcoat it with. Just as the success of a flower is dependent on its roots, the success of a problematic situation is dependent on getting to the root of the problem.

And the root of the problem is this: our students aren’t getting the mental help they so desperately need. Rather than evaluating our children, we are painting perfect pictures of the average day at an American high school, where learning to dodge bullets is just as necessary as basic arithmetic.

In addition to proving to be relatively ineffective, there are multiple studies that show that these seemingly harmless safety precautions draw more attention to school violence than they’re worth, and can actually lead to student violence. Think about it: if our schools are portrayed as maximum security facilities, then violence is expected, right? The idea of a copycat killer is exactly what it sounds like: see crime, emulate crime, and this idol-centric violence is more common than you’d think. For example, after the release of Netflix’s blockbuster hit 13 Reasons Why, a show featuring adolescent suicide, suicide interest spiked. NBC News reported “Following the show’s release, cumulative searches for suicide-related terms went up 19 percent, according to the new research. The phrase “how to commit suicide” went up 26 percent, “commit suicide” rose 18 percent, and “how to kill yourself” increased nine percent.” When violence becomes associated with pain relief and understanding, it becomes significantly more appealing to the most misunderstood of them all: teenagers.

Media expression of these acts of terror in schools can also lead to school shootings being seen as self-expression. In the ideal American high school, you’ll spot the American Dream itself: children working passionately to make a name for themselves, to become who they truly are. Sadly, many youths struggling with mental health issues see this from a reverse perspective and seek to make a name for themselves through a different, more blood-splattered route. Brian Warnick, a notable author on school shootings, proved this through his analysis of the manifesto left behind by Luke Woodham, who shot two students in 1997. Luke wrote, “I am not spoiled or lazy, for murder is not weak or slow-witted, murder is gutsy and daring.” Warnick points out that “the school became the place where Woodham thought he could express the gutsy and daring person he found on the inside”, indicating a probable motive for his violence. If we could redirect the attention of the media from the action of the crime to the appreciation for those lost, we may be able to erase this “spotlight” that troubled teens shoot for(literally), and we could likely reduce some of the romanticization of school shooters.

Another case against the piling on of safety precautions is that the actions are invasive themselves, which can anger the student population. As a high school student, I have multitudes of experience in this and have an inside look at the ineffectiveness of it all. After the Stoneman Douglass shooting of 2018, schools nationwide began a security frenzy, and rather than focusing on what schools can provide the most effective education, we entered the contest for the most effective maze for murderous adolescents. Many of these real-life booby traps are littered with privacy flaws, from the full name and student identification number displayed for the world to see, to the clear plastic backpacks required in some schools that create a nice little viewing area for anyone and every one of your personal belongings. Even victims of school shootings believe different action needs to take place. Stoneman Douglass junior Cameron Kasky wanted to showcase the extreme inconvenience these clear bags place on girls attempting to conceal feminine products, so he filled his entire bag with tampons and sanitary napkins (USA Today). An old rule at East Rockaway High School had students up in arms as well, when in 2018, student-athletes were required to leave their personal equipment in communal bins before they entered the school. Many students believed that this was an unnecessary procedure that was disrespectful to their private property, and furthermore, that it wasn’t actually keeping anyone safe. Most teens aren’t planning to carry out murder plots strapped with lacrosse sticks, and if they were, taking away that “weapon” isn’t going to stop them from finding an alternate one.

By giving students little to no say on the rules they are forced to follow, administrations everywhere are setting themselves up for failure. I see it all the time, the more us children are dehumanized and left to comply like dogs, the more we will bark back. Continually imposing rules does not equal a more compliant school environment, and if anything, it strains student-administration relationships.

Front door? Alarmed. Wing entrances? Alarmed. Tech rooms? Alarmed. But what’s really alarming to me is the blissful ignorance of the mental health of our students. Sure, we may keep possible weapons out of schools through checking bags at the door, but that doesn’t stop anyone from gunning the field Columbine-style or taking their murderous rage elsewhere. Here is an irrefutable clause: our youth are struggling severely with their mental health, and our schools are not currently equipped to deal with them. Metal detectors galore aren’t fixing the bigger picture; children’s thoughts don’t leave their minds at 8:00 AM. In order to enact any sort of long-lasting change, we must start with correcting the catalyst of these evil thoughts: the mind itself. The instillment of more guidance counselors and social workers in schools may help with connecting to our students, and may also identify any mental issues before they become a bigger problem. Additionally, teachers should be required to have education in recognizing the warning signs of mental illness. This would allow them to offer support to said students, and to hopefully be more accommodating to at-risk students and their needs. Socioemotional lessons (SEL’s) are a good start, but a struggling student is unlikely to share their beliefs and concerns among their peers, so they should be able to have access to more individualized direct attention. Furthermore, more grade bonding activities such as Rock Rivalry should occur (within pandemic regulations, of course) in order to help students create more connections and to ultimately bring the entire class closer together.

Eight-year-olds shouldn’t have to worry about their Twinkle Toes giving them away during a lockdown. Mothers should not be purchasing their children bulletproof backpacks. Little girls should not be carving “I love you mommy” into their skin so that when they’re shot, they can still be heard. They should be planning a career, not an escape plan for the one place where they are supposed to be protected. We need to make a change, and fast, before our precious I.D. pictures become the backs of memorial cards.

Sara Perrone • Jan 6, 2021 at 9:32 am

Spectacularly haunting! I especially love the intensity behind your call to action at the end.

Ms. Kenny • Dec 30, 2020 at 10:43 am

Thought provoking article, Maddy. Great job.

Kirsten Carman • Dec 18, 2020 at 7:21 pm

This is absolutely amazing and so well written.